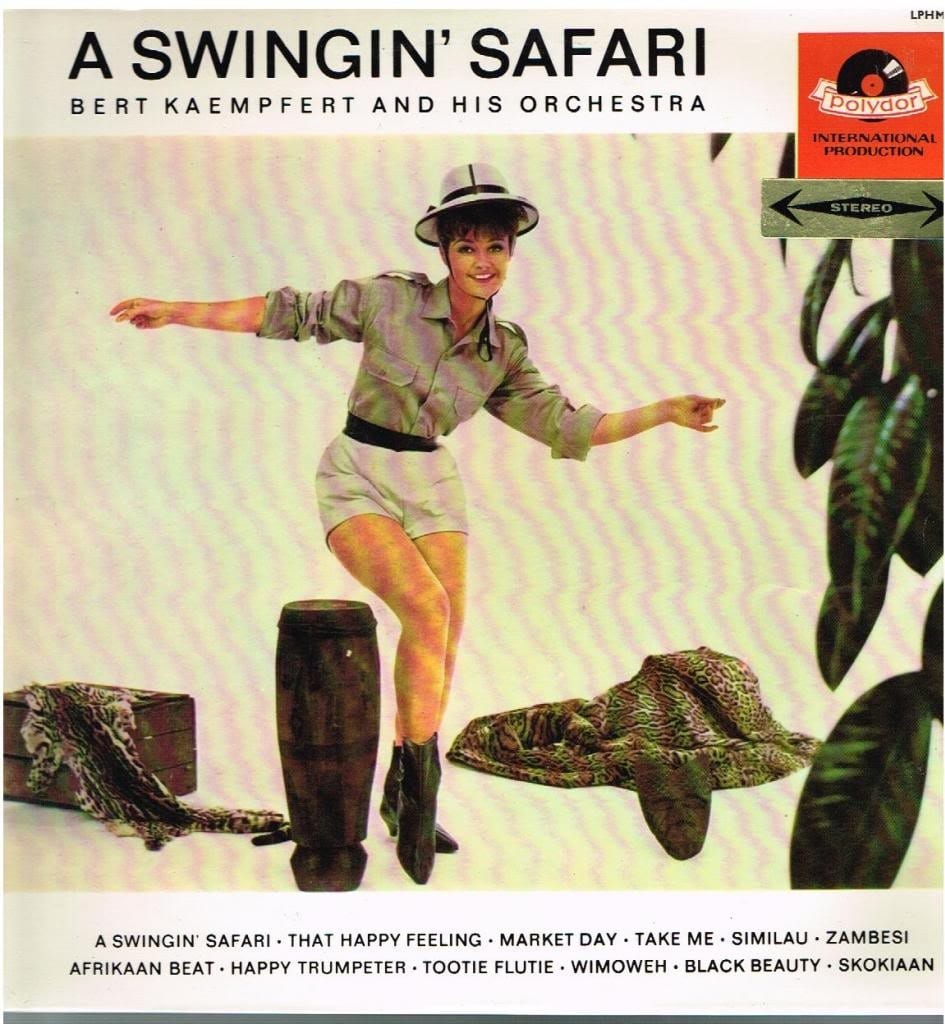

Janine Elliot takes a listen to the Album “A Swingin’ Safari” which was recorded in the Polydor Studio, Hamburg in 1961/62. The original analogue recordings from 1961/62 form the basis of Christoph Stickel’s unobtrusive “refurbishing” which aims to avoid any artistic intervention and here it is released on Reel to Reel tape from Horch House.

The last 30 years have seen the biggest changes in the recording industry. In a very short time it has moved away from analogue to digital; from reel to reel past Betamax,DAT and CD, now to computer storage and manipulation. My own career as a sound engineer started with chinagraphs, razor blades and sticky tape. I loved it. Recording straight to two track most of the time, meant that mixing on the SSL, Calrec or Neve decks at the BBC needed to be right first time, and if you needed to do retakes, then the settings of the previous take needed to be remembered, so that edits mid-way through a symphony didn’t suddenly move the viola section on top of the horns (they should be sat some 20 feet way from each other!)

I have amassed a collection of 18 reel-to-reel machines over the years, from Fidelity and Ferrograph to Tandberg and Telefunken. The top machine of choice, as any serious reel-head will know, is Revox and their professional arm Studer. My favourite personal machine is the Revox PR99, which is also the favourite of a certain Volker Lange, who owns two. He is one of the two owners of Horch House, a German company selling high quality vinyl, digital (24/96; 24/192; 64fs DSD) and now reel to reel master recordings using RMGI SM468 tapes on metal reels. There are, believe it or not, several other niche-pre-recorded reel to reel tape retailers around the world, The Tape Project from America and Opus 3 label from Sweden, being two that spring to mind. Back in Germany Volker Lange also is Managing Director for Lutz Precision, making precision machines for car industry, to which Horch House is the analogue audio division of this parent company. His role within HH is toward the hardware, and technical operation and production, and his colleague Thilo Berg, who founded the jazz and classical music label Mons Records in Trippstadt in 1991, deals with record deals content and software. Having worked as a music producer for Sony, BMG, Columbia and Universal, places him in the perfect position to get all those important master tapes he needs to create the different forms of copies available from HH. Recent deals have included Revox, who now sell HH master tapes on their website, although the Bert Kaempfert album under review here hasn’t yet made its way on to the Revox website. The album was originally produced by Polydor between 1961-2.

As well as these two directors is a third very important member of the team. Christoph Stickel’s job is to take those old, decaying, valuable master tapes and get them ready for making the copies. He calls this “unobtrusive” or “soft refurbishing”. Getting correct output level and a sound as close as the original master was itself on day-one is his talent. Once he is satisfied, he then uses the settings created on the master to make a direct, first generation copy onto reel to reel.

The history of reel to reels has changed considerably since I started my adventure with reel to reels in 1970. Manufacturers such as Agfa BASF, Philips, Racal, Scotch, Maxell, TDK, etc have long since stopped manufacturing tapes, and even RMGI (Recordable Media Group International) from Holland was taken over by Pyral from Avranches, Normandy, France in 2012, having morphed from BASF to EMTEC along the way. If I remember correctly, the SM468 (Studio Master) tape was originally a BASF product, far superior to the PEM468 from Agfa, which used to shed oxide on my tape machines. Many of my own tapes from the 60’s and 70’s are only fit for the bin, though I do have a Kodak reel of tape made from paper from the very earliest days of tape which looks as new now as it was when it was made. The album under review here, the Bert Kaempfert’s – A Swingin’ Safari was originally produced between 1961 and 2, I hasten to tell you well before I bought my own and first reel to reel Fidelity recorder. And whilst 53 years have been and gone this recording sounded as refreshing as the day it was made. HH now have an ever growing collection of tapes presently covering 23 jazz, 2 bigband, 5 Blues and 12 classical labels. All are recorded using CCIR equalisation onto RMGI SM468 Tapes on metal reels. A single tape will set you back around €298, while two-tape sets sell for €365, €550 for three-tape albums, and €598 for the four-tape sets. Lots of dosh, but as HH put it, it really is “a musical experience like only the sound editor and the artist himself could experience beforehand.”

But HH’s concern for not adding or taking anything away, rather “truth in sound” continues in all formats they sell. For example they convert from the analogue master tape directly into the 24/96 or 24/192 or DSD format digits without going near a PC or a Mac. All digital copies are provided on USB wafer cards, rather than relying on your internet to safely carry the digits to your home. And, they don’t convert 24/96 copies from 24/192, as some companies have done. This is as pure as digits can be. Similarly, with the reel to reel copies, the master tape is played on one Studer A80 playback machine and sent directly to one of 8 refurbished A80 tape recorders. No mixer, no compression, no limiting, no processing, no high-speed recording. Before recording the heads are demagnetised and all tape-guiding rollers and capstans cleaned. After the tenth recording the machines are all recalibrated. All this, combined with the real time recording process and editing leader head and tail takes time and hence reflected in the cost of the tapes. Andreas Kuhn, from Studer, sources and services the Studer A80’s, regularly monitoring them to check that they are working at their best.

Each first-generation copy is numbered and dated when it was recorded. Mine was No 11 recorded on 15/05/2015. The portfolio of tapes goes from Ella Fitzgerald, Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, and George Duke to works by Bach, Beethoven, Mahler and Richard Strauss. All your favourites played as they were originally recorded. All depending, of course, that your own tape player has been set up at its very best. And there are presently no tape machines being manufactured, so at the moment you need to visit eBay, unless by chance you kept your collection with your original turntable (which of course you regularly use now). The last machines being manufactured were Otari, Stellavox and Nagra. Michael Fremer last year announced at the Munich show that a famous Swiss manufacturer would start making machines again in 2015, but I haven’t seen any hints of that yet. I still live in hope. I used my PR99 and Sony TC766-2 for my review of the Bert Kaempfert.

It surprised me that a whole album would appear on a 10½ inch spool, but at around 34 minutes including all silences this was easily doable. The tape is stored tail-out, so that you have to rewind it all before you start to play. This is to prevent “print-through” of magnets lining up on the successive layer of tape. This was always a lot worse on early tapes that didn’t have a thick matt non-sticking backing, though without it, obviously being thinner, you could get more feet on the spool (cassette tapes didn’t generally bother with this backing). If it is stored tail out, then any print-through from a loud burst of sound would appear a microsecond after that original sound, and therefore be hidden. Not stored tail out, then after a time sitting on the reel that loud burst of sound will appear in the silence just before that burst of sound, if you follow me. Now, as a professional BBC sound engineer I would put yellow leader tape between each track, which also assists me if I need to quickly find track 4, for example. These tapes only have a red/white leader at the start and a yellow at the end. Finding tracks is guess work with your tape counter, though I only wanted to listen through from beginning to end, and which I did several times each and every day I had the tape. Whilst meeting international system of colour coding regarding the speed of the tape (red/white stripe is 15ips stereo, for example) it goes in opposite to my 25 years of Aunty training, where the red leader should be at the end. Nevermind, I could live with that. Indeed, the whole experience was like reliving my days in Broadcasting House and Maida Vale, and I thoroughly enjoyed it as I did the music. 52 years might have gone by, but the sound sounded just as fresh as in 1962. This was going back in time, just as I had listening to Mike Valentine’s ‘Syd Lawrence Orchestra’ vinyl from a few weeks back. Mike had played a reel to reel at the NAS show in Whittlebury and the sound was by very very far the best sound in the show. Both HH and Valentine had the right ideas, but whether we see a resurgence of reel to reel or direct cut vinyl, well, who knows. At least blank tapes are still being manufactured by a few companies.

To the sound; this was incredibly real. Noise floor was amazingly good (like most good tapes the SM468 is quoted as +6dB) with peaks flashing on my meter not giving any sign of reaching saturation or distortion. To be honest, I didn’t even notice any hiss. I was too busy just listening to the music. The biggest “noise” was from the mechanics of PR99, and even that didn’t annoy me, as I was too engrossed in the music. This was as real as it could get. No over-accentuated tops or unrealistic dynamic range, or digital zits. This was set just right for the music. Originally master tapes would be engineered for vinyl playback, which has a smaller dynamic range than CD, so the sound engineering on the original master tapes would have had an appropriate dynamic range in mind, just as whilst a BBC Radio Studio Manager my mixing was different for LW, AM, DAB or FM. Whilst the A Swingin’ Safari had no signs of compression or limiting, most meter movement was within the top 20dB, meaning tape hiss was not even a thought. Indeed I am so glad Dolby A or B, or compressed DBX i or ii were not chosen. They were always very hard to get absolutely right, and using these would limit even further the customer clientele. Indeed, unless the master tape was absolutely in original condition, and the Dolby and DBX was set exactly as it was originally, Christoph Stickel would have much more than soft refurbishing to do. All the 14 tracks on this album I had known before, which was rather embarrassing for someone who likes to proclaim to being ‘quite hip’. However, even sadder (for me) was that I kept returning back to this album to listen again. Tracks like ‘Wimoweh’ made me smile and think of my dad smoking his pipe and me watching a Bakelite Bush TV set next to the coal fire. Of course “A Swingin’ Safari” and “Afrikaan Beat” were internationally known songs that hit the pop-parade in the 60’s, and like Wimoweh were continually played on radio until the late 60’s until a group of 4 Liverpool lads seemed to get all the air time. The tapes tracked exceptionally well, especially in the lower frequencies below 100Hz, which is usually where bad mechanics and dirty tape path can show signs of irregularity. Bass was potent and tops were very clean showing that record bias and record heads were in tip top condition. Obviously my PR99 and Sony TC766-2 were set up as good as ever they could be, and never let me down once, giving me a chance to relive my youth. And boy, was it like going back in time. Whilst the music perhaps not my first choice of listening, I really did enjoy being young again, and would have no problem in paying out for a copy once I have saved up enough money from my paper round.

As someone who has copied 24/192 onto reel to reel so they sounded more natural, I can vouch for reel to reel tapes as an alternative to digits or vinyl. They are not cheap, but bearing in mind the cost of the blank tape and time taken in preparing the first-generation copy, this album, and any other in the series, is remarkably cheap to get so close to the original. Think of it as a hand painted copy of the Mona Lisa. It’s not the original, but it’s bloomin’ close.

Janine Elliott

You must be logged in to leave a reply.