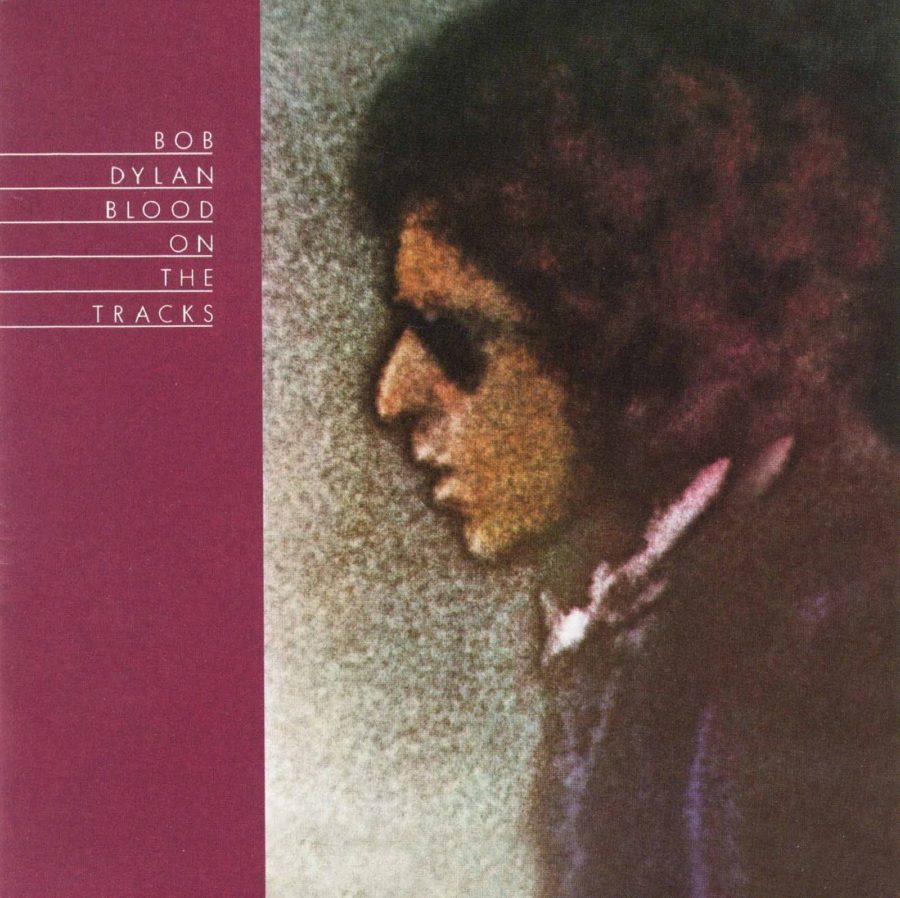

Earlier this month, Bob Dylan became the first musician to be awarded a Nobel prize for literature. John Scott celebrates by having a listen to Dylan’s 1975 album Blood On The Tracks.

If any living lyricist was going to awarded the Nobel prize for literature it was surely always going to be Bob Dylan. 75 year-old Dylan was awarded the prize for “creating new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition.” Dylan may not be the rock era’s most poetic songwriter – I’d argue that Leonard Cohen deserves that accolade – but there is little doubt that he is the most innovative and influential.

Right from his debut as a 21 year old protest singer in the thrall of Woody Guthrie, Dylan was a songwriting whirlwind, constantly honing his craft and refusing to stand still. Within three years he had taken ownership of the protest tradition on behalf of his generation, grown bored of it, and then alienated a large proportion of his fans by strapping on an electric guitar and belting out a new kind of photo-punk protest with a level of lyrical sophistication that was streets ahead of his contemporaries. In doing so, he made it almost obligatory for bands and solo artists to write their own lyrics, and for those lyrics to strive to be more than trite teenybop love songs.

From 1965 to 1969, Dylan spat out a run of three of the most brilliant albums that rock music has ever produced in Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde; changed direction with the almost biblical bleakness of John Wesley Harding and practically invented country rock with Nashville Skyline.

Something had to give. 1970’s Self Portrait was almost universally vilified on release (although it has been recently reassessed) and New Morning, Pat Garrett and Billy The Kid and Planet Waves – all of which have much to offer – were seen as lacklustre efforts. At the beginning of 1974 Dylan ended a seven year break from touring as he set out on a 40 date excursion, accompanied by The Band. During this time Dylan’s relationship with his wife Sarah became strained and the couple separated at the end of the tour. Pouring his thoughts into a series of notebooks, Dylan sketched out the songs that would become his next album Blood On The Tracks.

A large part of Dylan’s artistry lies in the ambiguity of his lyrics; by leaving room for interpretation, Dylan allows the listener to make the song what they want it to be. In Blood On The Tracks, Dylan takes his most personal lyrics and creates a series of songs that speak universally about love and loss.

On first hearing, the album can seem underwhelming. There is none of the barely-contained chaos of Blonde On Blonde or stylistic artifice of Nashville Skyline. The album was recorded in two four-day sessions; the first in New York in September 1974 and the second in Minneapolis in December – just three weeks before the record’s release- after Dylan decided to record five of the New York versions, having been persuaded by his brother David that they were too stark. The final version of the album consists of five of the New York songs and five from Minneapolis.

Dylan has denied that any of the songs on Blood On The Tracks are autobiographical. He inhabits most of the songs as the narrator of a story; sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third; sometimes switching from one to the other. Opening track Tangled Up In Blue takes a series of vignettes and weaves them into a whole. The characters in the verses may be the same all the way through or each verse may be a new scenario inhabited by new players. The events may be taking place in the narrator’s past or present. The whole becomes more than the sum of its parts and this is also true of the album itself.

Simple Twist Of Fate tells the tale of a couple brought together briefly by chance. Dylan’s character is left feeling that he has lost his “twin” after she leaves and he is doomed to wander through life hoping that fate will bring them together again. This theme is echoed later in the album in If You See Her, Say Hello in which Dylan asks a third party, perhaps anyone listening, to say hello on his behalf; to remind the unnamed “her” that he is still around, doing okay (but maybe not really). Like the character in Simple Twist Of Fate, he is searching on the off-chance that their paths might cross but this time the hope seems more forlorn and it seems obvious to everyone, apart from Dylan himself, that the contact he hopes for will never be realised.

There are not a lot of laughs on Blood On The Tracks but some light relief is offered in Lily, Rosemary and The Jack Of Hearts. This is a sprawling tale told almost in the form of a film synopsis – a style Dylan would revisit in Hurricane – set in an anonymous Western frontier town and featuring a complicated plot involving a gang of safe crackers, a diamond mine owner, his wife and his lover and the mysterious Jack Of Hearts whose presence triggers a serious of events culminating in jealousy and murder. I used to think this was just a throwaway song but the characters are drawn with such deftness that when I hear the song now a little film plays in my head. Like much of the album, it takes time before its qualities really become apparent.

This “slow burn” effect did the album few favours on its release. The use of anonymous session musicians and the lack of a defining style led to the album being described as “trashy”, “shoddy” and “incompetent “. Other critics, more perceptively, identified the album as signalling a new level of maturity in Dylan’s writing; he was no longer the spokesman for a generation, a responsibility that he had been burdened with and the expectations of which had no doubt contributed to his early-seventies slump. Dylan’s concerns were now closer to home and had sparked a new intensity in his writing.

Blood On The Tracks is now regarded as one of Dylan’s greatest albums. Over the following forty years he has continued to delight and infuriate fans and critics by refusing to be pinned down. With what appeared to be characteristic iconoclasm, Dylan took a couple of weeks to acknowledge the Nobel committee’s award but has now come forward to say that he was rendered “speechless” by it. And just as he has always done since that debut album 54 years ago, Dylan is polarising popular opinion; can rock lyrics be classed as literature? Perhaps the answer is best left blowing in the wind.

John Scott

You must be logged in to leave a reply.