Record Equalisation Explained

If you don’t know your NABs from your RIAAs or your Microgroove from your Orthacoustic, don’t panic as Janine Elliot is here to explain the history and the science behind vinyl equalisation.

Over the years we have had to put up with different ‘standards’ in our single aim for enjoying music. Whether noise reduction systems such as Philips DNL, Dolby B, C or A, DBX I, II or ADRES for our cassettes and reel to reels, NAB or IEC EQ for reel to reels, MP3 (which is actually MPEG-1 and MPEG-2 Audio Layer III, with an infinite number of compression algorithms, set up by the Moving Picture Experts Group) and FLAC, ALAC, DSD, MQA and other lossless formats. You get the point. Many of us playing our records will be aware of the main types of cartridges, MM, MC, MI and ceramic, but not so many will be aware that over the years there have been more than 100 types of equalisation for the humble record cartridge in order for it to play a record correctly.

If you have ever put your ears next to your stylus you will notice the “top heavy” response, with nothing particularly audible below mid frequencies. Today’s standard of record EQ is the Recording Industry Association of America RIAA curve¹. That curve tries to “normalise” the response so that after playing the grooves it all sounds normal and flat. In the recording the RIAA curve has around -20dB taken off the signal at 20Hz and rising logarithmically to +20dB at 20,000Hz. That means in playback the EQ needs to amplify by 20dB at 20Hz and attenuate by 20dB at 20kHz. The reasons for the equalisation are fourfold; Firstly to cut the bass down otherwise the stylus would be jumping up and down and probably throw the needle out of the groove, and then likely ruin the record. Secondly, the larger groove size of the lower frequencies might join with an earlier or later rotation (called over-cutting), and thirdly, it means that with a reduced ‘mean width’ of each groove you can get more minutes recorded onto your record. Finally, if you boost the higher frequencies relative to the bass you can get an increased signal-to-noise ratio; a bit like Dolby B, and incidentally FM radio (pre-emphasis and de-emphasis in transmitters and receivers respectively).

The first use of EQ in the recording process was as early as 1926 from Bell Telephone Laboratories when they noticed that even in the disc-cutting recording process things were not flat; the amplitude is higher as the bass lowers and decreases as the frequencies get higher. Whilst creating playback EQ curves in wind-up mechanical record players was not possible, the replaceable needles of the gramophones could be purchased in different shapes to create either “loud tone” or “soft tone” sounds. Incidentally, the term “put a sock in it” originates from putting a sock in the trumpet your gramophone to reduce the level of sound.

As early as the 1940’s EQ curves have been employed in records to improve the listening, all of which have reduced the bass and increase the treble. Before the universal RIAA curve and particularly from the 1940’s, each record company applied its own equalization curve; this meant that there were over 100 combinations of turnover and roll-off frequencies in use. In all these different systems 1000Hz is considered 0dB. It does, therefore mean that playing certain records designed for different EQ settings will sound either bright or ‘bassy’ when decoded using the generic RIAA curve of today. When the Columbia LP was released in June 1948 they noticed that there was more bass boost or pre-emphasis below 150 Hz, and similarly the RCA Victor 45 rpm disc released in February 1949 noticed this had a different recording characteristic, due to the different recording speed. They decided to use the “New Orthophonic” EQ setting whereas Columbia decided to use the “LP” setting.

The various EQ curves used before RIAA came to the rescue in 1954 were from the main record making companies, such as Columbia, Victor, Decca (FFRR-78 and FFRR-LP) Microgroove, RCA and EMI; and even broadcasters and organisations such as BBC, NBC (Orthacoustic), NAB and IEC used their own curves. For example, RCA Victor reduced it by 18.6dB at 30Hz and by the time it got to 15kHz was up17.2dB, meaning the EQ needed to be set in reverse to flatten it all. As a contrast, the London Gramophone Corporation reduced 30Hz by 13.2dB and raised 15kHz by 15.1dB. Playing on a modern RIAA curve would mean that in the second example the sound would be graphically more like a happy smile with boosted bass and treble.

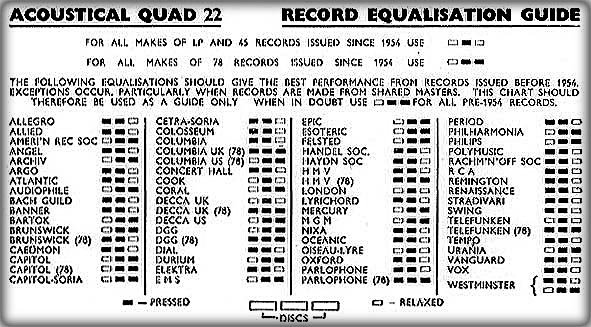

The importance of playing your records with the correct EQ cannot be overstated. If all your records are post 1955 then you would have little to worry about. Older records should therefore be played with the correct EQ for each record. Whilst RIAA curve was issued in 1954 it wasn’t until 1958 that all the stalwarts finally gave into the new curve. Hartley-Turner, a company claimed to have coined the phrase “High-Fidelity” in 1927 in reference to their wireless receivers, introduced their Tone Control Unit between 1950 and 1954 to allow players of gramophone records to tailor the sound of each record to match the correct shape. Similarly, another British company Lowther introduced their BT/2 tone control in 1948 to do the same. Both were very limiting adjustments, and it took manufacturers such as Leak to make concerted efforts to get exact EQ for specific record types. For example, their early 1952 Varislope I (£12.12s.0d) had LP (for old LPs pre-1955), 78B (British 78’s) and 78A (American 78’s); the Varislope III from 1957 (£15.15s.0d) had 78E (European 78’s), NARTB (for playing LPs by Artist, Capitol, MGM, Westminster, Tempo M33), LP and RIAA. The 1960 Varislope Stereo (£25) added 78NE (New European 78’s and also work on Columbia LPs pre 1955). My favourite is the Tannoy Autograph control Unit of 1958 (£16.10s.0d) which had a multi position EQ control for BRIT 1 (for EMI 78s), BRIT 2 (for DECCA 78’s), Columbia 78’s, RCA (78’s and LP), Columbia LP, RIAA, AES and NAB. The Quad 22 featured three buttons which allowed the user to select 4 common equalisation curves, by selecting different permutations of the 3 buttons, which allowed matching to a large number of 78 and 33⅓ derivatives. Just to be different, several manufacturers decided to stick with their own EQ curves well after the letters RIAA became de facto, including Columbia, Decca, CCIR, and TELDEC’s Direct Metal Mastering. As a result a few Phono Equalizers made today offer options to play these.

The TELDEC (Telefunken-Decca) DMM recording process was even more complicated, because these records were cut directly to metal (not the usual lacquer) using a specially adapted Neumann disc cutter (VMS82) which had the groove cutting done at a different angle than normal, meaning that using a standard cartridge set at the standard playback angle of 15–22.5° would change the frequency characteristics.

But, the problem of matching is not limited to the correct EQ, or indeed the angle of the stylus to the record. If the cartridge is not properly loaded with the correct resistance and impedance from the phonostage, it will not playback flat. Choosing phonostages with user-adjustable cartridge loading is not just for gimmicks, and something only looked at seriously by manufacturers since the invention of the CD that was supposed to supersede it. The RIAA feedback loop in the amplifier assumes that it is getting a perfect negative curve to begin with. Phono amps with an incorrect loading of the cartridge can cause a frequency response off normal by 6 to 10 dB due to improper cartridge loading.

Whilst we have spent years improving phonostages to get hifi nirvana, with passive stages costing £1000 and much more, there is also a movement towards digital and computerised phonostages. Companies such as PSpatial Audio have a Macintosh based High-Resolution Audio App called ‘Stereo Sauce’ offering historic equalisation algorithms to match any type of 78 or 33, and a number of Windows/Android based products are making excellent phonostages that would have been unheard of just 10 years ago. The phonostage in Convert Technology’s ‘Plato’, reviewed by Hifi Pig recently, is an example. Will the future of the RIAA curve lie in digital form, only time will tell, but the future of the algorithm looks set for a long future yet, however it is arrived at.

Janine Elliot

Read more Retro Bites with Janine Elliot