Janine Elliot takes a listen to the STS Digital reel to reel copy of Jazz Masters Volume 1

The days of reel to reel tapes were the best part of my life, editing with china-graph and razor blade on a Leevers Rich or Studer reel to reel at Aunty Beeb. I could cut at the correct angle without even using an EMI editing block; I was so used to the 60 degree angle I could do it in my sleep! Training fellow BBC Studio Managers on the new-fangled A807 in the 1980’s was met with some disapproval that this technology was ‘too modern’ with auto locations and zero-stops just too confusing. Laughable that a few years later far more complex computerised recording techniques would mean considerably more training to use correctly. Listening to reel to reel tapes in hi-fi shows presented by recording engineers such as Mike Valentine (an ex BBC sound engineer himself) show that the format still is the most realistic method of audio production, even if rather hissy at times. Audiophiles around the world are now beginning to realise the virtue of the format. Perhaps even cassettes will return again if we can get Nachamichi Dragon sound quality without the cost. One drawback with both formats is the signal to noise ratio, with Dolby B and C noise reduction favoured against cassette decks with neither. That extra S/N ratio shouldn’t, but invariably did result in a less clear and realistic top end. Whilst Dolby A was much better and used for reel to reel tapes it was very costly so most people with 16 reel to reel tape machines like me won’t have a means of decoding “A” recorded tapes today. I preferred DBX 1, but that’s for a future Retro Bites column. Jazz Masters 1, comes to you with no noise reduction, which is good news.

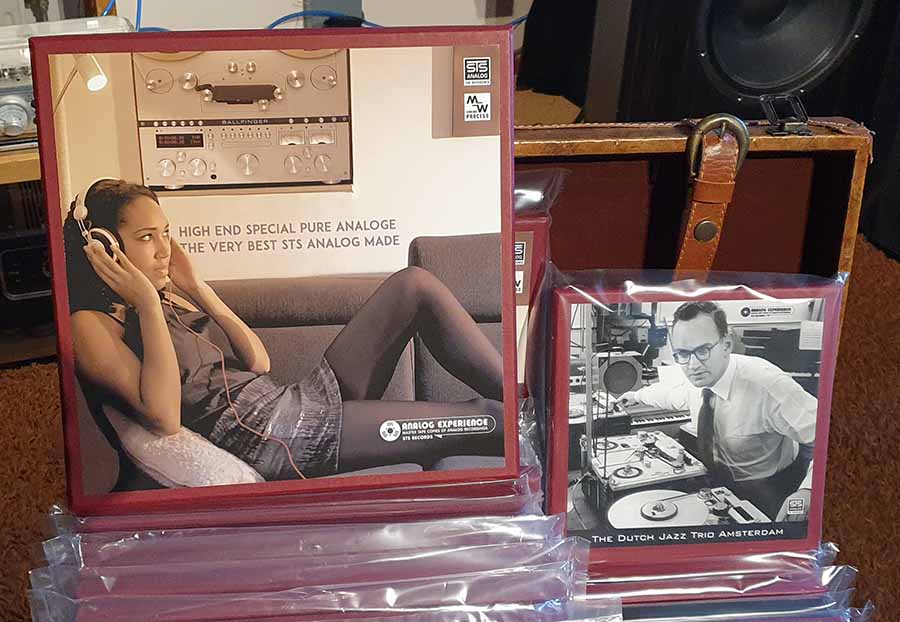

Fritz de With, founder of STS Digital who produce this reel to reel tape, as a child spent time at Philips watching engineers record albums and even helping set up microphones in the studio. On one occasion he helped the sound engineers set up a mix, and put a microphone close to a Lesley speaker on a Hammond organ, to be told he actually needed to put two as the unit has two revolving speakers giving that definitive sound, hard to replicate on one microphone, and nor indeed today on digital keyboards. This recording from STS has a Lesley speaker organ, probably a Hammond B3 or C3 closely mic’d giving a more human and realistic sound, as if you were there yourself, something a modern sound engineer/home recordist would not even attempt. That is why recordings from the 60’s-70’s are my favourites and often still sound exceptionally good on less favourable playback formats such as CD. As a child Fritz had recorded religious orchestral and vocal music, such as Handel’s Messiah, and his relationship with Philips continued when he was 25, going back to them to learn how to record other types of music such as jazz. Previously, having already set up his own recording studio with a catalogue of over 460 LP (long play) length recordings, he sold them to Philips in 1978 and bought a BMW. His long-term contacts with Philips led to advice as to even which machines to buy (such as the iconic 10 ½” tape Studer A77, and the unusual 9” maximum tape 600SH, from a German company based in Villingen, with its own built in basic fader mixing facilities) and eventually to him mastering and copying on Philips machines. Interestingly, STS use Philips machines for the master and copying machines, rather than a suite of Studer A80’s that one would perhaps expect.

Recording Technique

The name ‘STS’ is short for “Studio Tape Sound” and Fritz and wife Nettie set up STS Digital some twenty years ago as a result of many, many years of recording orchestras and musicians in the Netherlands. The “Digital” in the name refers to reproducing many of the titles on CD, SACDs. Many CDs are recorded using their own STS Digital MW Coding Process to make them sound more “analogue”. They also have recordings available in good old analogue DMM 180gm vinyl. Whilst Fritz had sold all those recordings to Philips, he kept the copyright, and as Philips no longer produces records, he can. His love of recording audio and recording it well was why he started it all in his youth, and why he later formed STS Digital. Whist he loved using microphones close to the instruments – something I will mention again later in relation to this recording – he noticed that so many recordings are just so close mic’d that they lose the surroundings they are in, which is vitally important for the overall sound. Recorded in this manner they can lose some of that purity and warmth, with a harsh sound when too close and without any ambience. He wanted to just hear the sound of musical instrument in the way it should be heard in the room in which it is being played. My own amateur recordings onto my Teac X1000M or Akai 4000DS tape recorders back in the 70’s used coincident-pair microphone techniques with two angled microphones sat just far back enough to pick up the ambience of the room. The warmth and musicality would put many of todays’ mass-produced home studio digital work to shame. I was therefore so pleased in the 21st Century to have a chance to review several of the STS tapes. The first of them is ‘Jazz Masters 1’ recorded luckily without any noise reduction, on a ¼ inch half-track 15ips LPR35 tape from French tape manufacturer Recording the Masters, based on the original Agfa and BASF formulations. These £249 high-speed copies are produced appropriately on home-grown Philips reel to reels; Philips EL3501 master copied onto a bank of six N4522 slave recorders and using CCIR equalisation via a Telefunken M15a. The EL3501 dates back to 1952 in its valve version, with transistor versions added later, and which is the variant that STS have. Whilst Philips isn’t perhaps considered on such a high level as Studer, this 4-motor machine was found widely in studios in Europe, including the BBC. And, the N4522 was probably the best domestic reel to reel recorder made by Philips, dating from 1979, and the ¼ track N4520 version was even sold at Comet, I recall, though I settled for a Teac X1000M instead. Masters from the EL3501 are firstly recorded onto the excellent Telefunken M15a reel to reel recorder using Telefunken Telcom noise reduction and then that is used to make the copies on the bank of six N4522 tape machines, meaning the original tape won’t get over used. This companding noise reduction system is similar to DBX, though unlike DBX I and II which are broadband, ie single-band, companders, the Telcom system works at different levels for different frequencies. Whilst this system works better than DBX, it was not so widely used, although Nakamichi used the basic High-Com version in a few of their cassette decks (labelled as Nakamichi High-Com II Noise Reduction System). Toshiba/Aurex did a similar system called ADRES which was used in a number of their own cassette decks and all could be far less detrimental to the top frequencies than Dolby B and C if the machine isn’t tracking properly. The beauty of the systems above is that there is no need for calibration.

As well as 15ips copies of Jazz Masters 1, Slower 7½ips versions on 7” tapes are available at £179, though obviously with not quite so good audio quality. They even do 1/4 track versions to special order. The 15ips reels themselves are excellent gold/black or silver/black spools, which are twice as thick as the usual Racal, EMI, Scotch, Maxell or TDK of old. Fritz noticed that conventional metal reels are so thin that they can “ring” like an instrument if you tap them. They also will bend easily which can catch the tape as it moves off or on to the reel, particularly when spooling at high speed, something I myself had noticed from a child. His own designed reels made in Germany also have 5 screws joining the centre spindle rather than the conventional 3, so are much more secure. I love them, though they are not cheap. My only dislike is that the rear half is black meaning it is hard to see the tape itself; it makes threading tape and seeing how much is on the reel quite difficult. But this spool is well worth having, and is available separately for purchase.

Music

This excellent album originating from two recordings made in the 1970’s includes Buddy Tate on tenor sax, Milt Buckner on electric organ or piano and Wallace Bishop on drums; all effortlessly performing with a tight saxophone, a close mic’d organ sound (complete with vocal noises from Milt and the sound of him hitting the notes on the keys) and a well-spread drum kit. The timely electric organ reminded me of the days of 2-manual organs reticent in many homes in the 60’s and 70’s for wannabee Klaus Wunderlich’s. The sound might be dated but it was just so enjoyable. What Fritz has done is remix these closely mic’d recordings by adding reverb from a rare Philips/Marantz AX1000 “Audio Computer”. This DSP (digital signal processor) analyses the sound and processes EQ and ambience, recreating concert halls such as Symphony Hall, Boston, Royal Albert Hall, London, Concertgebouw, Amsterdam, and Opera House, New York, to name just a few. It can even enhance the soundstage using its “Stereo Control” feature. Of five hundred AX1000’s having being made Fritz has 2 of them. The added ambient atmosphere Fritz uses is both appropriate and correctly proportioned.

Sometimes simplicity is the best, and this trio of Milt, Buddy and Wallace excelled with ease and space to allow the music to live and breathe in a way that allows the listener can get to know and almost take part in the music. The noise from Milt and the finger punching of the keys I found very involving. This recording might not have Dolby A or B (thank goodness) but any tape hiss disappeared from my senses as soon the music took over. Indeed, this is an extremely noise-free recording; Fritz making sure that the record level is as high as can be attained without any saturation of the tape and without the replay heads on the players themselves ending up being over-drenched in magnetic patterns. The Sony TC-766-2 meter only hit +3dB at the peaks and my Revox PR99 never showing any flashing red light “this is just too loud!” indications, though it got close. Fritz’s ability to get recording level just right was well noted by me. Never does the sound come across over modulated. Indeed, even his CD recordings are made so that they don’t get higher than -2dB. A similar philosophy was used at the BBC, with reel to reels not exceeding PPM6 on the Peak reading meters. The BBC moto of “Nation Shall Speak Unto Nation” was revised by BBC sound engineers to “Nation Shall Peak 6 Unto Nation”.

Whilst there are 8 tracks labelled on the SP (standard play) tape I actually counted 10, though that didn’t worry me; the last one being faded out as it got near the end of the reel. Fritz wants to make sure as much music gets onto each tape. The CD version includes 15 tracks. Jazz Masters 2, 3 and 4 are already available with a fifth being produced when Fritz gets around to it.

The recording starts with the laid back “When I’m Blue” with running commentary from Milt uttering phrases including “yes indeed” and “careful now” and “Hit it Blue” as he works rhythm’s between himself, the saxophone and the drums, as if they are in deep conversation. The close mic’ing not only picks up the words and noises from Milt, but also his fingers hitting the keys; the instrument almost becoming part of his own body. You just need a smoky room and an audience to make it totally believable. One of my favourites on Jazz Masters 1 is “September Song”, composed by Kurt Weill with lyrics by Maxwell Anderson, introduced by Walter Huston in the 1938 Broadway musical production Knickerbocker Holiday, and also the theme tune of a well-loved (and one of my favourite) 1989-94 TV series “May To September”, with Buddy Tate performing miracles on two saxophones simultaneously this is an epic studio recording, all in a very slow and laidback style, as if we have just as many months to play it from beginning to end, not that I got bored; this was an emotional performance with the Milt’s keyboard skills this time acting as organ donor to the sax. “Midnight Sun” continues the theme of close mic’ing of the keys of the piano, with much level change in the music using the organ foot-pedal, hearing Milt’s fingers tapping away, actually gave the music an extra feel of reality and depth to the music, rather than an annoying addition. The descending piano notes were like drops of rain showing perhaps there were a few clouds amidst the midnight sun. This music really does show the personal (finger) touch, even if this time Milt’s vocal embellishments aren’t making quite such a riposte as a few earlier tracks. The saxophone is missing here, and the drums are carefully and sparingly added to the musical painting. “That’s All” has a closer drum kit balance, giving yet another set of colours to this acoustic palette. “Sophisticated lady” is a complex recording with a full orchestral band complete with glockenspiel. “Angel Eyes” brings the party back to the original organ, sax (duo) and drums, with some great mic’ing, especially of the sax, and this time with microphone closer to the organ loudspeaker. Whilst some more detail of the recording itself wasn’t available on the box for such an expensive collection of music (such as when and where they were recorded, microphones used, and all the musicians names) it didn’t stop my enjoyment of the music. To be honest, it was recorded so long ago that Fritz didn’t have any information, just as my own recordings in the 70’s and 80’s barely had a few words on the spines of the boxes.

A pound short of £250 might worry your bank manager but your tape recorder will love it. In total I listened on a Revox PR99 and A77, Sony TC 766-2, and Ferrograph Logic 7 half-track high speed recorders, all set up for CCIR playback and the sound was equally good on all, with no sign of over modulation, with a meaty bass end as only reel to reel can do and all covering all frequencies with equal aplomb. My review sample had arrived tail-in meaning that some print-through was audible at the start of tracks but that didn’t stop my enjoyment. When purchasing, the tape will arrive tail out and whilst that is rather a pain having to rewind the tape at the start of your performance it does mean you don’t need to at the end! By being tail out, any loud notes that print through from one layer of the tape to the next will appear after the commencement of the sound meaning it will be inaudible.

Conclusion

I thoroughly enjoyed playing this recording from STS. It took me back to the good old days when we took pride in making special recordings on reel to reels that I thought was consigned to history. Whilst reel to reel machines are becoming popular on eBay, the new Ballfinger M 063 tape recorder is now fact not fiction after 4 years of R and D to get it finally into the shops. So this could at last be the time to consider the ultimate in analogue. This recording not only sounded so good, complete with all the noises from Milt, but it was also a great selection of performances that you will want to keep playing. Just remember to store the tape tail out.

You must be logged in to leave a reply.