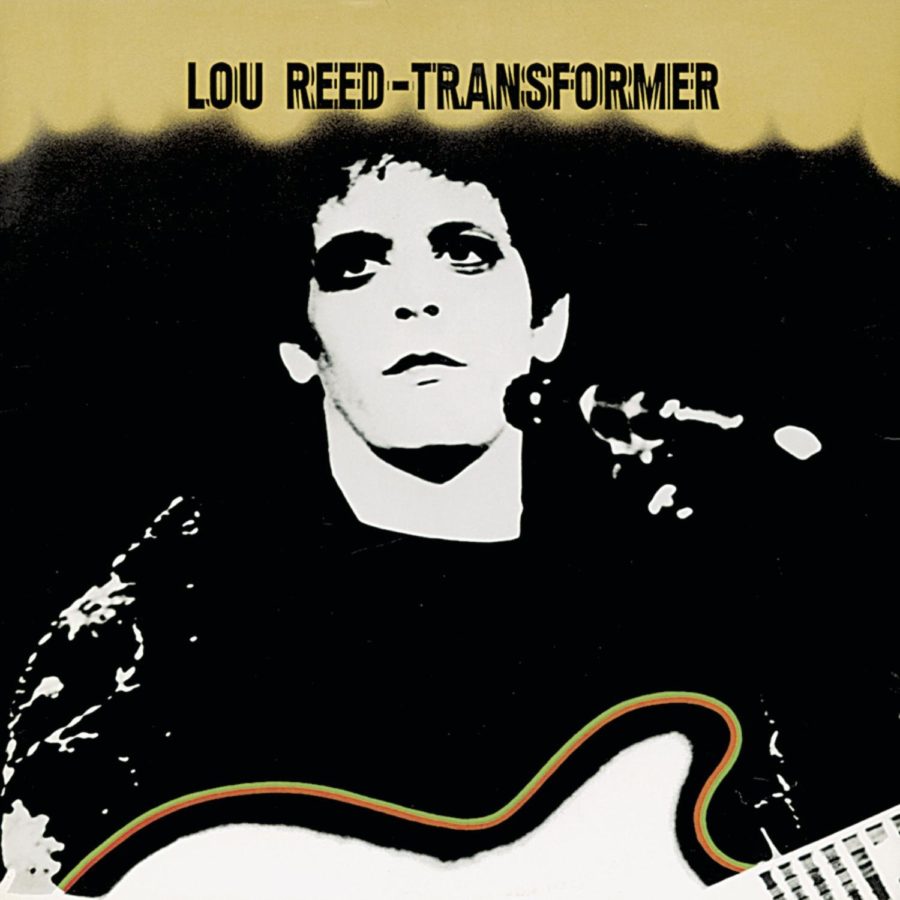

Never one to avoid an obvious cliché, John Scott takes a walk on the wild side and reacquaints himself with Lou Reed’s 1972 hit album.

I first encountered Lou Reed in the spring of 1976 thanks to an interview in Melody Maker with journalist Allan Jones. I was a naïve thirteen-year-old at the time; I knew nothing about Lou Reed, I’d never heard of The Velvet Underground and I had no idea what a Lou Reed record might sound like. By the time I had finished reading the interview I was still no better informed on what a Reed’s music might be like, but I had learned a few things: I’d learned that Allan Jones was totally in awe of Reed; that Reed had nothing but contempt for Jones – regularly referring to him during the interview as a “little faggot” – or in fact for anyone who wasn’t Lou Reed; that Reed liked to take lots of drugs and had a six foot four transsexual girlfriend called Rachel. While the interview was a thoroughly fascinating Reed-related read, I was left with the impression that Reed was a deeply unpleasant individual and I had no interest in finding out any more about his music.

This changed just over a year later when I fell head over heels for The Modern Lovers’ Roadrunner single and read that Reed and his old band The Velvet Underground were a huge influence on The Modern Lovers’ lead singer and guitarist Jonathan Richman. I sought out a Velvet Underground compilation and gave it a listen. I was a bit torn; I liked some of the songs like Sunday Morning and Waiting For My Man but I wasn’t really sure that it was my thing and I mentally filed it away as something that I might come back to at some time in the future.

My next encounter with Reed was during the death throes of a drunken party maybe five years later. Slumped semi-consciously in front of an electric fire I managed to barbecue my leg while listening to Transformer. It might not have been up there with Reed’s own rock and roll excesses, but you have to start somewhere. The scars on my leg took about 18 months to heal, my fondness for Transformer’s trashy glam aesthetic never faded.

Before we look any further at Transformer, it might be useful to recap just a little on Reed’s earlier history. Reed was born in Brooklyn in 1942 to middle class parents and developed a keen interest in rock and roll, rhythm and blues and do-wop music from an early age, playing in several bands while at high school. His education was interrupted by what was put down to a mental breakdown, treated by electroshock treatment. Reed later said: “That’s what was recommended then to discourage homosexual feelings. The effect is that you lose your memory and become a vegetable. You can’t read a book because you get to page 17 and have to go right back to page one again.” Reed resumed his studies at Syracuse University where he studied under the poet Delmore Schwartz who would remain a lifelong influence. After he left Syracuse, Reed started work as a staff songwriter for Pickwick Records. A band, The Primitives, was put together to record The Ostrich, a song that Reed had written to parody the dance craze records that were popular at the time. Welsh musician John Cale was a member of The Primitives and he and Reed began a partnership that led to them forming The Velvet Underground with Sterling Morrison, whom Reed had met at Syracuse on guitar and Maureen Tucker on drums. The band hooked up with artist Andy Warhol and became an intrinsic part of the New York art and music scene. Although never particularly commercially successful in their lifetime, The Velvet Underground went on to be one of the most influential bands in rock history.

The Velvet Underground were never particularly stable, Cale leaving in 1968 after 2 albums and Reed himself bailing in 1970. Reed initially took a job as a typist with his father’s accountancy firm before signing a contract with RCA records and recording his first self-titled solo album in London between December 1971 and January 1972. This proved to be, for the most part, a somewhat sterile revisiting of some Velvet Underground tracks that had featured in live performances or on demos but had never made it to a studio record. The album was recorded with a bunch of seasoned session musicians, including improbable appearances from Steve Howe and Rick Wakeman from Prog supergroup Yes.

There was nothing in this debut solo album to suggest that Lou Reed had anything to offer anyone who was not already a committed fan of his work with The Velvet Underground. Nothing to indicate that Reed might have any chart success or, indeed, an ongoing career. Fortunately for Reed, London in 1972 was the hotbed of Glam Rock. While Reed had been recording his solo debut, David Bowie had been working on his glam masterpiece The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars with Mick Ronson. T Rex had released Electric Warrior in 1971 and the UK pop charts were full of glam hits from Gary Glitter, The Sweet and Slade.

Perhaps more than any other genre, Glam relied on self-mythology and artifice, from Gary Glitter’s tinfoil pantomime persona to Bowie’s considerably more fleshed-our starman alter ego. Glam provided Reed with a route to reinvention, one that allowed him to draw on the louche demimonde that The Velvet Underground had mined, reinvented for a new audience. Reed had met Bowie in New York in September 1971. Bowie was a huge fan of The Velvet Underground and was keen to meet Reed. Lou was less keen but the pair got on well and became friends. When it came to recording Reed’s next album, it made perfect sense for Bowie and his sidekick Ronson to produce along with, perhaps even more importantly, Bowie’s long-time co-producer Ken Scott. While Bowie and Ronson contributed musically to the album, it seems likely that it was Scott who provided its overall sound. Scott certainly needs to be credited for the sound of those famous Doo-De-Doo-De –Doo backing vocals in Walk On The Wild Side. “By the time it came to mixing “Wild Side”, I was so sick of hearing the “doo doos” so many bloody times that I had to do something just to relieve the boredom of it” Scott said. “ I had this idea of them coming from way back in the distance and walking forward finally singing it right in your face. I started off with just the reverb signal which I kept at the same level during the mix, but I had the source background vocal level come up and up until you hardly hear the reverb at all and they’re almost dry and in your face.”

Like Reed’s previous album, Transformer pulled on Velvet Underground-era songs. Four of the album’s ten songs were written while Lou was still with the band; Andy’s Chest and Satellite Of Love had been recorded by the band and Goodnight Ladies and New York Telephone Conversation had been played live. Reed had so far portrayed his sexuality ambiguously, but on Transformer he embraces Glam’s extravagance and seizes every opportunity to ramp up the camp to the max.

Opening track Vicious takes the kind of riff that Reed used on Velvet Underground songs such as Sweet Jane and Rock And Roll and pares it down to a razor’s edge. Reed’s tone is that of a slighted Bowery drag queen. Perfect Day is one of the album’s most iconic songs. Superficially a bland love song, Perfect Day is actually a serenade to smack. Some years later, Bowie would turn this idea on its head when transforming Iggy Pop’s own homage to heroin, China Girl, into a pop song about a Chinese girl. Walk On The Wild Side is the album’s signature song. Although I’d said that when I’d read that interview back in 1976, I’d had no idea of who Lou Reed was, I realised in retrospect that I had in fact heard Walk On The Wild Side on the radio. It seems incredible that in the comparatively prudish times of the early Seventies, a song that explicitly mentions oral sex would fly so far over the head (no pun intended) of the BBC Radio One censor. The song tells the tales of some of Andy Warhol’s Factory acolytes but it’s popularity arguably lies not in the stories it tells but in Herbie Flowers’ famous twin bass lines – one swooping up the neck of a double bass and the other dancing around the dusty end of his 1959 Fender Jazz bass. Highlights of side 2 include the pure pop of Satellite Of Love and Wagon Wheel, the high camp of New York Telephone Conversation and Goodnight Ladies which sounds like it could have been lifted straight from the score of Kander and Ebb’s score for Cabaret. Possibly coincidentally, Mick Rock’s accidentally overexposed shot for the cover of the album echoes Joel Grey’s haunted Master Of Ceremonies from that film.

Transformer gave Reed his biggest commercial hit and almost certainly saved his career. In true Lou Reed style, his next record was the bleak song cycle Berlin of which producer Bob Ezrin commented “Wrap this turkey up before I puke.” Reed went on to record a double album of guitar feedback, Metal Machine Music, further alienating himself from the audience who had been hooked by transformer’s Glam allure. Reed remained true to his own artistic muse throughout his career and, despite his treatment by Reed, Allan Jones remained a fanboy. His enthusiastic review of 1986’s Mistrial sent me rushing out to buy the album on the day of release. It remains one of the worst in Reed’s discography. Still, I’ll always have Transformer and the hazy memories of that party.

John Scott

You must be logged in to leave a reply.